Every once in a while, you’ll hear a wizened veteran of our sport waxing eloquent about the ‘good ol’ days’ of mountain biking, when wheels were small and brakes were actuated by cables. “Sure, they didn’t stop you that well“, she’ll say, with a faraway look in her eye, “But that was part of the challenge!“. While vintage bikes may be regaining some of their former popularity among the ironic-mustached crowd, the industry-wide adoption of hydraulic-fluid operated brakes has allowed our sport to progress to the point it’s at today… with the majority of riders capable of stopping before slamming into trailside obstacles.

1994 XC World Champs. Can we all take a second to be thankful this is no longer the norm?

If you’re the proud owner of a bike equipped with hydraulic actuated disc brakes, congratulations. If you’ve ever looked at those brakes and wondered what goes on inside them, then this article is for you!

Let’s start with the basics: How hydraulic disc brakes work. Broken down as simply as possible, when you pull the brake lever of a hydraulic brake, the lever blade depresses a piston inside the lever body, which forces hydraulic fluid through the brake line to the caliper, where it forces two more pistons together, compressing the brake pads against the rotor.

Hydraulic disc brakes are generally more powerful than mechanical (cable actuated) disc brakes, as the hydraulic fluid does not compress under load (transferring all of your squeezing power directly to the brake pads), and this fluid actuates two pistons, rather than one. With more power comes more control, and with more control comes more fun on your bike.

As with any advancement, there are some things that one loses when moving to hydraulic disc brakes (the constant fear of crashing into stationary objects being one). Hydraulic disc brakes require more maintenance than mechanical brakes, due to the intrusion of air (which does compress) into your brake fluid (which doesn’t). Hydraulic brakes are also more difficult to install onto internally-routed frames, as they require bleeding (of the brake system, not the installer) when the line is cut. If you live in fear of performing maintenance on your bike, and your nearest LTP Sports dealer is a parsec away, a brake like the TRP Hy/Rd might be a better bet for you, as its semi-mechanical design cuts down on the need for regular maintenance.

The TRP HY/RD semi-mechanical disc brake blends cable and hydraulic technologies for easier installation and lower maintenance.

So, assuming that you’re convinced that you made the right decision in going hydraulic, here are some useful things to know.

-

With great power, comes great modulation

As we discussed, hydraulic fluid doesn’t compress like air, water, or brake cables. This means that you don’t suffer any loss of power between you pulling the brake lever and the pistons clamping down on the rotor. However as we all know from watching ‘fail’ videos of people flying over the handlebars of their bikes, too much power all at once isn’t ideal. Modern disc brakes are designed to allow modulation- the ability to finely control how much power is exerted- to keep you from locking your brakes up every time.

Modulation isn’t for everyone, however. Some riders, myself included, prefer brakes to be more touchy, and to provide the entirety of the braking power as quickly as possible. Brake systems like TRP’s G-Spec DH and Trail tend to have more of an on/off feel (more power, less modulation) than brakes like SRAM’s Code or Guide brakes.

-

Not all hydraulic fluids are created equal

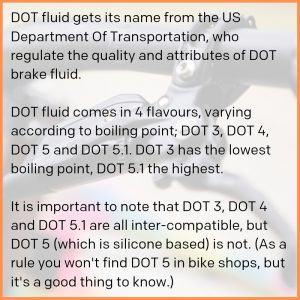

There are two different types of hydraulic fluid used in bicycle disc brakes; DOT fluid and Mineral oil. DOT fluid is the standard hydraulic fluid used in brakes, and mineral oil is exactly what you think it is- very similar to the stuff you’d buy at the pharmacy. Both fluids are incompressible and resistant to heat, making them ideal for use in brake systems. However, that’s about where the similarities end, and it should be noted that mineral oil and DOT fluid systems are NOT COMPATIBLE. (You can’t change the hydraulic fluid in one system for another.) That said, you can use this information to inform your decision about what type of brakes to buy, and it can also guide your purchase of aftermarket hydraulic fluids for when you do need to bleed your brakes. To break down the differences between the two systems, let’s look at some aspects of brake fluid.

Your brakes will be clearly marked with the fluid that they’re designed for.

Boiling Point: Brakes create a lot of heat, especially on long downhill sections. When a fluid gets too hot it turns from an incompressible liquid to a compressible gas, and braking performance suffers accordingly. The boiling points of the different DOT fluids and mineral oils vary significantly, so it’s a good idea to keep these in mind when choosing your next brake system. The boiling point of DOT fluids depends on whether the fluid is brand new (dry) or whether it has been exposed to water (wet), which is why two boiling point numbers are often given. (Mineral oil doesn’t absorb water, so only the dry boiling point applies.) Maxima DOT fluid has a particularly high boiling point due to its general awesomeness. If you want better braking performance from your DOT brakes, run Maxima brake fluid.

Water solubility: On a long enough timeline, water will get into your brake system. Water is incompressible, just like brake fluid, but its much lower boiling point means that your brake performance can suffer as soon as the brakes heat up. Water gets into the brake system through microscopic pores in brake lines, past seals and through seams in the caliper and lever bodies. DOT fluid will absorb water over time, up to 3% over the course of 2 years, giving them a spongy feel under heavy use. While mineral oil is hydrophobic (won’t absorb water), the water that does get into the system tends to amass near the brake caliper (the lowest point in the line), where it heats up quickly and can cause even more sudden brake fade. The takeaway here is that you should bleed your brakes once a year, no matter what type of fluid they use.

Popularity: Both DOT fluid and mineral oil are widely available, but DOT’s use in the automotive world guarantee easier availability and lower prices. While the mineral oil you can pick up at the pharmacy might seem like a good idea, keep in mind that, unlike DOT fluid, mineral oil is not government regulated, so non-bike-specific products likely won’t perform nearly as well. TRP’s Mineral oil is a great way to pick up a whole lot of high-quality bike-specific mineral oil at a decent price.

Mineral oil is non-corrosive, so you don’t need a ton of safety gear to work on it. (though eye protection is still recommended).

Shelf Life: DOT fluid absorbs water over time, where mineral oil does not. Thus, an open bottle of DOT fluid will last about 2 years before it should be thrown out, but a bottle of mineral oil is good for years.

-

The need to bleed.

Any hydraulic brake system will require bleeding once a year to remove air, water, and contaminants trapped in the system. Bleeding involves forcing new fluid into the system, and removing the old contaminated fluid, without allowing air to enter the system. The easiest way to perform a brake bleed is to take your bike to your local LTP Sports dealer and let them do it. The second easiest way is to purchase a bleed kit and try it yourself! Keeping watching this space for an instructional video.

Two of the best brakes in MTB – TRP’s Mineral Oil G Spec DH and SRAM’s DOT Fluid CODE RSC

So there you have it; as much information as you’ve ever wanted about hydraulic brake systems. If you have further questions, you can always message us on social media, or head into your local Live to Play Sports dealer for the lowdown from their experienced mechanics!